- Other Issues

- April 14, 2010

- 9 minutes read

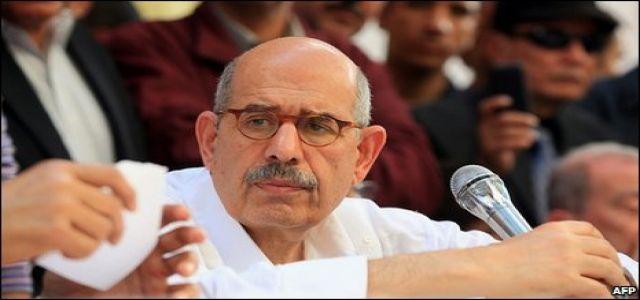

Egypt ‘thirsty for change’ says Mohamed ElBaradei

Mohamed ElBaradei, emerging as a contender to Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, tells BBC Middle East editor Jeremy Bowen he will only consider standing for office if the constitution is changed.

Cairo was its usual self, sprawling, chaotic, noisy, dirty and magnificent.

It is the Middle East’s city that doesn’t sleep, exploding with human energy.

For Cairo’s poorest citizens – and there are a lot of them – most of that energy goes into extracting a life out of very unpromising circumstances.

Foreigners who turn up expecting to get things done can end up deeply frustrated.

Deep frustration, followed by a swift return to Europe is probably what the regime of President Hosni Mubarak would like for Mohamed ElBaradei, the former head of the UN nuclear watchdog the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

His calls for change in Egypt have led to an internet campaign to push him to run for president, an idea that is not going away.

The Mubarak regime seems sufficiently alarmed to portray him as a near foreigner, out of touch after a career abroad.

‘Panicking’

Mr ElBaradei’s political credibility in Egypt and around the Middle East comes from the time when he questioned the claims about weapons of mass destruction that were being used to justify the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

In his garden in an elegant, though relatively modest villa near the pyramids, he is relatively relaxed about the roasting he has received in some parts of the official media.

“I think they are panicking [because of] the increasing snowball effect of the call for change,” he said.

“You see the vilification of me. I thought I was vilified by the Bush regime. Compare that to the vilification I am getting in my own country. I am the devil incarnate!”

The level of attention – from his supporters and from those in the regime he is clearly making nervous – is despite the fact that the Egyptian constitution does not allow an independent to stand as a presidential candidate.

Only officials of parties that have been licensed and established for at least five years are eligible.

Change

Mr ElBaradei says that he will only consider a run if the constitution is changed. He says he would rather boycott next year’s presidential election than take part in a system that he believes is designed only to preserve the status quo.

Egypt, he says, is at a dead-end after almost 30 years of President Mubarak.

“People are thirsty for change,” he says. “I am not going to be part of flirting with democracy.”

Even President Mubarak’s supporters accept that change is coming.

Professor Hossam Badrawi, a prominent figure in the ruling National Democratic Party who owns one of Cairo’s top private hospitals, puts it delicately.

“Anyone being in power for so long creates around him those who become comfortable with the status quo. It is important for the people to see change, that’s human nature.”

Tenacious grip

It took an official broadcast on Egyptian TV of a thin but definitely living and breathing President Mubarak to end rumours that he had died after recent surgery to remove his gall bladder.

The president has been in power for nearly 30 years.

His grip on power is tenacious and he uses an emergency law that puts drastic restrictions on citizens’ rights to make sure it stays that way.

He has never lifted the state of emergency that he imposed when he took office after the assassination of President Anwar Sadat in 1981.

The emergency law is often directed at the Muslim Brotherhood, which is the best organised and largest opposition group.

It is illegal but tolerated as long as it doesn’t rock the boat too heavily.

If its leaders and activists try to break out of the narrow limits the regime allows them, they can expect a spell in one of Egypt’s nasty jails.

‘Pregnant’

But Mr Mubarak will be 82 next month. He is not in the best of health and his friends and enemies are thinking about what comes next.

“Egypt is like a woman expecting a baby,” said Ayman Noor, who stood against President Mubarak in flawed elections in 2005.

“She is eight months, three weeks and six days into the pregnancy. Everyone knows a baby is coming. They just don’t know what it will be like.”

Mr Noor was jailed for four years on charges of fraud after he took on President Mubarak.

The government says he went to jail because he was guilty. He puts it down to the continued harassment of any potential rival by a president who runs a highly repressive regime.

Unstable region

Mr Mubarak, his critics say, has tried to make himself into a modern pharaoh. The assumption is that, health permitting, he will stand again in 2011 unless he steps aside in favour of his son Gamal, who is being groomed for the job.

Mohamed ElBaradei believes he is making it harder for the regime to renew itself by passing the presidency on to the younger Mubarak.

The question now is whether the opposition, in whatever form, can make some inroads into the regime’s power when President Mubarak goes – and how his departure affects this unstable region.

Egypt regards itself as the leader of the Arab world, but in recent years it hasn’t punched its weight.

President Mubarak’s successor might change that.

At the very least there is uncertainty ahead for the Americans and their allies, including Israel, who have relied on President Mubarak to keep Egypt quiet.